|

|||||

| Home | Research | For Teachers | HISTORY Level 1 Level 2 Level 3 |

PRINCIPLES Level 1 Level 2 Level 3 |

CAREER Level 1 Level 2 Level 3 |

| Gallery | Hot Links | What's New! | |||

| Web Administration and Tools | |||||

|

|||||

| Home | Research | For Teachers | HISTORY Level 1 Level 2 Level 3 |

PRINCIPLES Level 1 Level 2 Level 3 |

CAREER Level 1 Level 2 Level 3 |

| Gallery | Hot Links | What's New! | |||

| Web Administration and Tools | |||||

The continuity equation stated above is a very handy equation useful in almost

any engineering application. It shows how a person can relate geometric conditions to flow

conditions at any given point were the area and the velocity are known. But for other

applications it is easier to obtain a pressure reading at a given point rather than

pulling out a ruler and measuring the area at a given point. In fact if the area has a

complicated geometry (for example a rupture in a tank) an exact measurement of it could be

a tedious process. Lets assumed for this study that instead of a geometry reading, you

have a reading of pressures to work with. The question being: Is it possible to calculate

velocities is the pressures are known or vice-versa ? And the answer to that is: yes. The

equation that would relate pressure to velocities (actually one of the most useful

equation in engineering) is called Bernoulli's equation and is given as:

![]()

Bernoulli's equation is only valid if one assumes the following: incompressible fluid

(fluid velocity less than one third the speed of sound) and inviscid flow (this just means

that the point in question along the flow is going to be away from where the flow and the

object come into contact). This equation basically tells us that, as the flow progresses

from one point to another, an increase in speed will be accompanied by a decrease in

pressure. Lets look at the same converging tube as before. It is possible to prove that

pressure will decrease as velocity increase. This was proved in the example before. But in

this case all we have to prove is that the pressure change between station 2 and station 1

is negative,

![]()

where: ![]() (from the results shown before)

(from the results shown before)

So, starting with Bernoulli's equation and solving for the pressure difference:

![]()

Since V1 is less than V2 then the subtraction in the parenthesis

will yield a negative result, therefore as velocity increases pressure decreases.

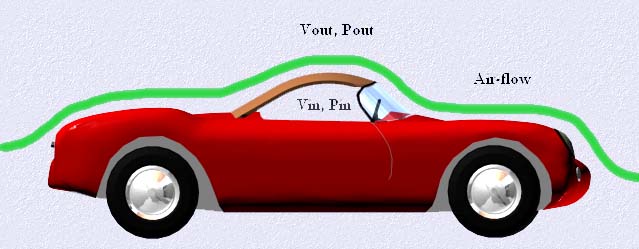

Another example of this concept is when a convertible car, with the top on, is in

motion one would see that the cover would "pop" outward.

This is because the velocity of the outside air is higher than the velocity of the air

inside the car (actually the velocity of the air inside the car is nearly zero). Therefore

the pressure inside the car is much higher than the pressure on the outside of the car,

thus the car top will "pop" outward.

It is best to look at an actual example in order to obtain a better understanding of

the Bernoulli's equation as well as the continuity or momentum equation. Lets begin with

wind tunnel applications. Wind tunnels are basically tunnels that have a fan attach to one

side of it, in order to blow air to the other end of it. A model of an airplane or car is

place in the air stream in order to measure its aerodynamic characteristics.

A sea level, low-speed wind tunnel of circular cross section with a diameter upstream

of the contraction of 20 ft and a test section diameter of 10 ft. The test section is

vented to the atmosphere (sea level pressure is 2116 lb/ft2). If the working

section velocity is 180 mph, calculate the following:

a). Upstream section velocity.

b). Upstream pressure.

Lets draw a wind tunnel first.

a). From continuity equation,

Then

![]()

b). From the Bernoulli equation,

![]()

![]()

![]()

Note that you need to change the 180 mph to feet per second.

![]()

![]()

An airfoil is moving through the air at 355 km/h at sea level. The atmospheric pressure

is 102,325 N/m2 and temperature is 27 C. At a point on the airfoil upper

surface the local velocity is 420 km/h.

a). Determine the pressure at the upper surface point.

b). If the pressure in part (a) is the average upper surface pressure, how much

lift per square meter (referred to ambient pressure) is being provided by the

upper surface ?

c). If the average speed on the lower surface is 320 km/h, what is the pressure

and the average lift per square meter on the lower surface ?

d). What is the total lift per square meter of wing ?

Lets draw first the airfoil,

In the SI system, temperature must be expressed in Kelvin and velocities in m/s.

a). From the Bernoulli equation,

b). Lift per square meter, upper surface = 101325 - 99038 = 2287 N/m2.

c). On the lower surface,

Lower surface lift = 102397 - 101325 = 1072 N/m2.

d). Total lift per square meter = 2287 + 1072 = 3359 N/m2.

The total lift for the example above was 3359 N/m2 and also as seen in the example above the angle of attack is 0 degrees. The angle of attack is the angle that the wing makes with the incoming flow. As the angle of attack increases, the lift also increases. But if the angle of attack increases beyond a certain angle, the lift will suddenly decrease in a phenomenon call stall. The maximum angle is also known as stall angle. The stall phenomenon is better understood by looking at the graph of lift versus angle of attack (Figures below).

![]()

![]()

As seen in the figures above, as the angle of the wing increases, the lift increases until the stall angle is reached. If the angle of attack is increased beyond the stall angle, the lift will decrease. Many of the aircraft crashes around the world happen because of the stall phenomenon. The phenomenon is also seen in propeller blades as well as in the inside of air breathing engines. This is because the main components of air breathing engines are wing-like in shape (although much smaller than aircraft wings) and if the conditions are correct they also suffer the same phenomenon as the their bigger brothers. Small aircraft crashes can also be attribute to stalling of the propeller which would leave the aircraft without power.

More on bernoulli (click here)

The information in this section has been extracted from several sources. Those sources have been contacted and permission to use their material on our site is pending. However, the format in which this material has been presented is copyrighted by the ALLSTAR network.

Send all comments to ![]() aeromaster@eng.fiu.edu

aeromaster@eng.fiu.edu

© 1995-98 ALLSTAR Network. All rights reserved worldwide.

Updated: February 23, 1999